Environmental Monitoring and Reporting is Not Enough.

The establishment of thresholds that trigger subsequent action is critical to protect the features of Muskoka that we value.

By Keith Somers.

Most people can identify the features of Muskoka that they value – majestic pine trees, healthy forests, clean lakes, Loons, Lake trout, Bald eagles – these are our valued ecosystem components (VECs).

As managers, we should monitor the condition of our VECs and regularly report on their status and trends over time. Monitoring can negatively impact some VECs, however, and so our monitoring often focuses on surrogate indicators. For example, the condition of a White sucker fish population might serve as a surrogate indicator for the condition of the Lake trout population.

Where monitoring indicates a healthy White sucker population, we could infer (in the absence of angling pressure) that the Lake trout population is also healthy.

Although there are many VECs, there are only two classes of indicators – stressors and effects (or responses). For example, lakes can be evaluated by monitoring stressor-based indicators like total phosphorus concentration.

Numerical guidelines or criteria are available for many stressors, so evaluating the status of VECs using stressor-based indicators is often straight forward.

By contrast, effect-based indicators, such as the condition of a fish population, are more difficult to evaluate because guidelines or criteria are largely absent. Interpretation of effects-based indicators can be done, however, by comparing results from the sampled area with the normal range of variation observed in minimally impaired, reference (or control) ecosystems.

If White sucker condition falls within the normal range of variation for White sucker populations in minimally impaired lakes, then we can assume that the White sucker population, and by inference, the Lake trout population, in the subject lake is healthy.

The regular monitoring and reporting of stressor- and effect-based indicators is not complicated.

Guidelines, criteria and benchmarks provide a context to evaluate indicator status and can be established with a combination of scientific and public input, such that interpreting the status of our VECs can be routine.

Unfortunately, regular audits of status and trend do little to actually protect our VECs.

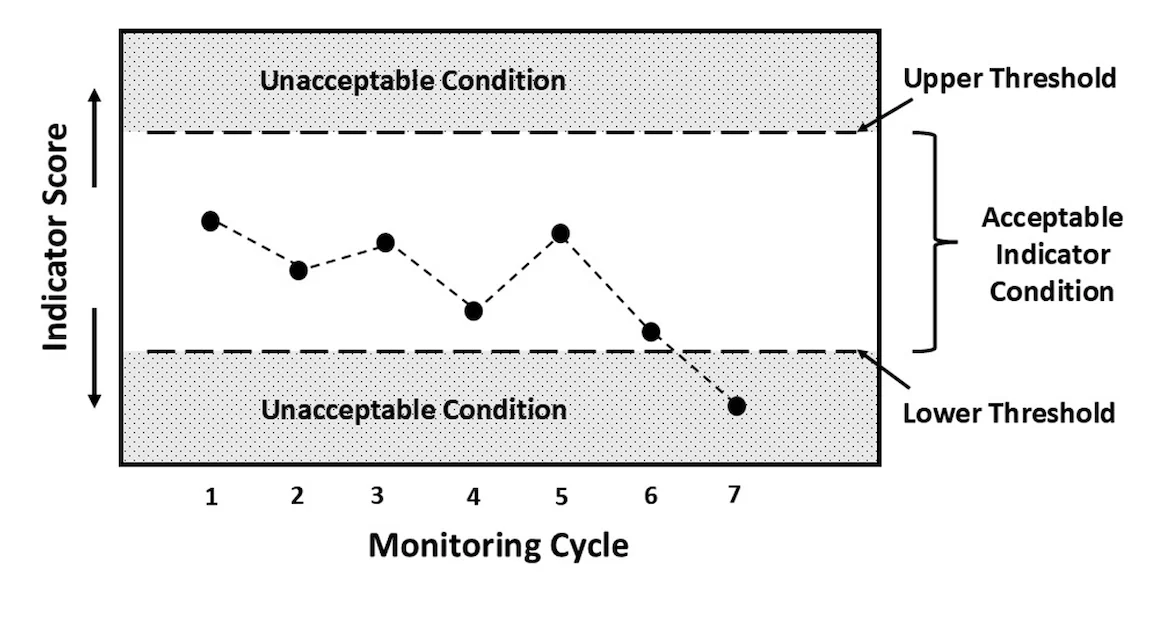

Protection will require intervention when monitoring results suggest a departure from an acceptable state. Boundaries around the limits of acceptable change are called thresholds (see figure below).

For example, we might define thresholds for White sucker condition as the range of values encompassing condition in 95% of White sucker populations from minimally impaired, reference lakes.

If our audit indicates that condition has crossed a threshold, this finding should trigger follow-up action.

The first action usually involves a repeat of the audit to confirm that the observed departure was not an error, or a one-time anomaly. If the threshold exceedance is confirmed, additional monitoring to identify the magnitude and geographic extent of the exceedance is warranted.

Where magnitude and extent are a concern, follow-up studies to investigate the cause (and candidate solutions) may be necessary. Once the cause is identified, appropriate interventions to protect the VEC can be implemented, and monitoring continued to assess the effectiveness of the management intervention.

The identification of VECs and associated indicators is an important precursor to a successful monitoring program. But monitoring and reporting audits without preestablished action thresholds do little to protect our VECs.

Environmental monitoring and reporting requires the use of indicators with action thresholds that trigger adaptive management to protect resources in unacceptable condition. In essence, the establishment of thresholds that trigger subsequent action is critical to protect the features of Muskoka that we value.

This article is part of Muskoka Watershed Council’s summer 2024 series on “Living in Our Changing Watershed” published on MuskokaRegion.com. This week’s contributor is Dr. Keith Somers, a retired aquatic ecologist who worked at the Dorset Environmental Science Centre for more than 25 years and continues to work as an adjunct professor at the University of Toronto. The series editor is Dr. Neil Hutchinson, a retired aquatic scientist, Bracebridge resident, and Muskoka Watershed Council director.