What’s Wrong with the Current Management of Our Watershed?

Too Many Managers and No Common Plan.

By Patricia Arney.

The Muskoka River Watershed stretches from its headwaters within Algonquin Park to its outlet to Georgian Bay. This watershed needs holistic governance that stretches across municipal boundaries and across environmental issues – land-use planning, water quality, climate change. Current governance is not holistic, and my purpose here is to reveal its subdivided, compartmentalized nature, by showing just how many separate jurisdictions are involved.

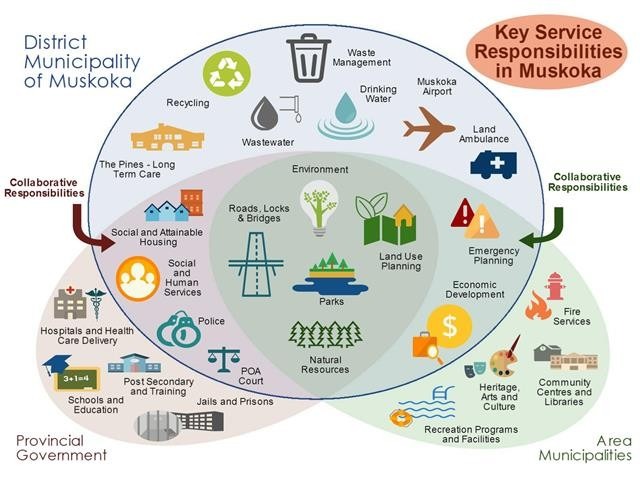

Land use planning and environmental management decisions in our watershed are governed by several levels of government.

First comes the Provincial Planning Statement, fondly known as the PPS – formerly the Provincial Policy Statement – which sets the policy foundation for regulating the development and use of land across the province.

The PPS states that all land use planning decisions, whether made by municipalities, provincial agencies or others “must be consistent with” policy statements in the PPS.

Some PPS policies set out positive directives – goals that must be met; others set things that must not be done. Some policies use enabling language, such as “should,” “promote” and “encourage” to provide for planning approaches that are desirable but not mandatory.

As a result, despite all municipalities following the PPS, there is considerable variation in how the PPS is interpreted and implemented. This is appropriate given the enormous range of places and planning needs across the province of Ontario. But the flexibility also means that neighbouring municipalities can make quite different planning decisions.

In addition, The District Municipality of Muskoka, as an upper tier municipality, has an Official Plan that provides broad guidance for the six municipalities within it: Lake of Bays, Muskoka Lakes, Georgian Bay, Gravenhurst, Huntsville and Bracebridge. It states that these lower tier municipalities may implement their own land use policies, so long as they do not “conflict” with the PPS or the District Official Plan.

Watersheds do not respect municipal boundaries, and the Muskoka River Watershed does not even lie wholly within the District of Muskoka. There are seven other municipalities involved in the ‘oversight’ of the watershed: Archipelago, Seguin, McMurrich/Moneith, Perry, Kearney, Algonquin Highlands, and Dysart et al. Also, Indigenous communities, such as Wahta First Nation, set their own land use planning policies in consultation with the Federal government. Crown Land is managed directly by the provincial government.

Planning policies of lower tier municipalities within the watershed, but outside the District of Muskoka, also must not conflict with the PPS. Some may have to conform with planning directives from their own upper tier, but not from the District of Muskoka.

While municipalities have primary responsibility for land use planning, the provincial government includes multiple ministries with responsibilities governing other aspects of environmental management. MECP1, MNR2, MTO3, MAH4, MOI5 – a veritable alphabet soup of ministries – each make management decisions within the watershed. There are also some federal ministries in the mix. All operate independently of each other and of municipalities.

In this sense, our watershed suffers not from a lack of governance but from too many governors and no comprehensive oversight of the ecology of the watershed.

Significant environmental issues like stormwater management, wetland protection, agricultural land protection, shoreline and infill development, invasive and endangered species, forest health, economic development and so on are being managed without an overarching watershed plan. This results in ‘gaps’ in the protection of the environment.

In 1971, 25 municipalities came together to form the District of Muskoka. In 2001, the District of Muskoka helped form the Muskoka Watershed Council to guide the management of the watershed. It is now time for all levels of government and the myriad of NGOs6 who work so diligently to protect Muskoka’s environment to collaborate to achieve the sustainable social-ecological system we want and need.

This is article #19 in First Steps on the Path to IWM, the current series of articles from Muskoka Watershed Council edited by Dr. Peter Sale. Author of this article is Patricia Arney, long-time member and former Chair of MWC. Patricia has been active in promoting sustainable environmental stewardship through many years as a resident, business owner, and municipal councillor.

This article was originally published on MuskokaRegion.com on April 21, 2025.

- Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks ↩︎

- Ministry of Natural Resources ↩︎

- Ministry of Transportation ↩︎

- Municipal Affairs and Housing ↩︎

- Ministry of Infrastructure ↩︎

- Non-governmental Organizations ↩︎