‘Ecological osteoporosis’ in our lakes and forests

Calcium is a critical element for all life.

By Dr. Neil Hutchinson.

We have a problem with “ecological osteoporosis,” or low calcium levels, in our forests and lakes. This is a concern because calcium is a critical element for all life, being a key structural component of our cells and bodies and a required element for our nervous system.

Trees contain about one per cent calcium, fish 2-8 per cent, and clams and crayfish more than 20 per cent.

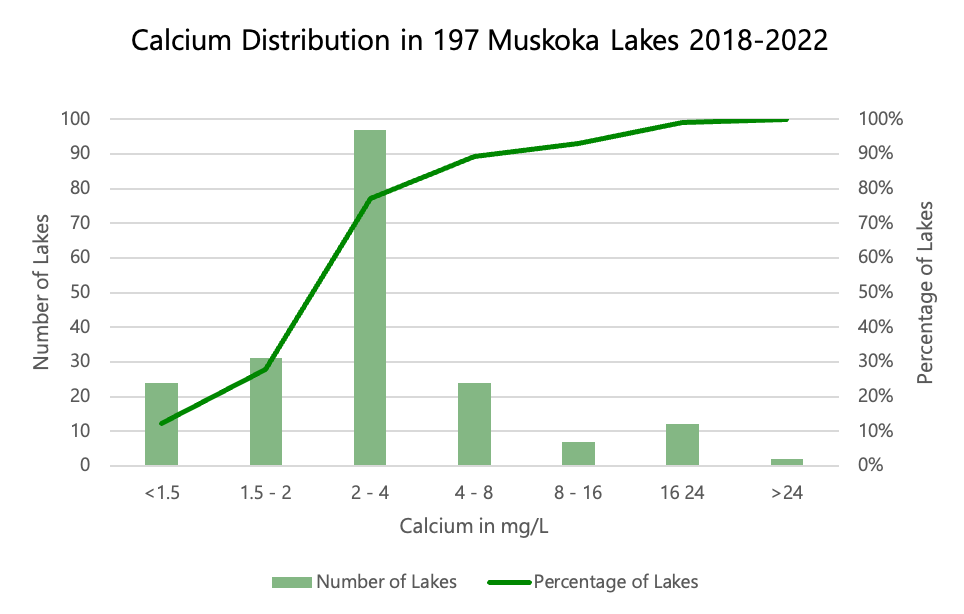

Muskoka Watershed Council’s 2023 Watershed Report Card concluded that 28 per cent (55 of 197) of the lakes sampled by the District of Muskoka were classified as “vulnerable,” with calcium concentrations below 2.0 mg/L, such that reproduction of sensitive aquatic life was threatened.

Twelve per cent of our lakes were below 1.5 mg/L, such that survival and reproduction of those species was unlikely.

Data examined for the report card only goes back to 2017, insufficient time to assess any trend in calcium levels. However, scientists at the Dorset Environmental Science Centre report average decreases of 40 per cent for their Muskoka study lakes since 1981. Climate change is likely to worsen this situation.

The calcium status of our watershed is a function of natural and human factors. The low levels and slow leaching rate of calcium in the 1.5-billion-year-old granitic bedrock beneath us limits how much calcium is made available by weathering.

And glaciation thousands of years ago stripped our soils bare, such that current soils are thin. Emissions of acid rain across North America leached calcium from our soils for five decades, and removal of calcium by logging and changing land uses over the approximately 150 years of Muskoka history resulted in further removals.

These leave our forests and lakes weakened by calcium loss, such that aquatic life is threatened. Our forests are less able to withstand wind, snow and ice, and are limited in their ability to remove carbon dioxide from the air as a buffer against our warming climate.

“Ecological osteoporosis” is a rare case where the goal of management should be to increase, rather than decrease, the concentrations of an element in the environment.

Muskoka’s calcium status is a good example of the need for an integrated watershed management approach that addresses our geography and history, and the linkage between our lands, forests and waters and our activities.

We can’t control our bedrock or our glacial history — they define Muskoka and resulted in the forests and waters that we enjoy.

We successfully tackled acid rain through abatement programs across North America in the 1990s. Our current forestry practices are well managed and considered sustainable, but they still represent ongoing losses of calcium from our forests.

We are therefore left with two management needs: restoring the historic calcium deficit in our soils, and preventing further losses from present activities.

Five years ago, Friends of the Muskoka Watershed initiated the first program of residential wood ash recycling in Canada — diverting wood ash from our landfills and spreading it in the forest to restore the calcium that was lost. They have collected more than 32.2 tonnes of wood ash and safely applied it to our forests.

Scientists at Trent University have published research showing uptake, incorporation and resultant benefits of the calcium to the trees. Citizen scientists are currently measuring how trees on their properties respond to controlled ash additions, and a large addition of wood ash was applied to a sugar bush in Bracebridge late in 2023.

Still, these remain modest first steps. To restore calcium levels across Muskoka will require a substantially scaled up supplementation program as an integrated part of environmental management across the watershed.

This is the fifth in a series of articles from the Muskoka Watershed Council on “The State of Our Watershed” published on MuskokaRegion.com. Each explores environmental issues and management challenges revealed in the 2023 Muskoka Watershed Report Card. This week’s contributor is Dr. Neil Hutchinson, a retired aquatic scientist, Bracebridge resident, and director with the Muskoka Watershed Council, Friends of the Muskoka Watershed and Georgian Bay Forever.