The harsh effects of winter de-icing salt on trees

By Javier Cappella.

Cooler nights and shorter days trigger a response in trees to let them know it is time to shed their leaves and become dormant for the winter. The flush of colours in the autumn quickly gives way to defoliated canopies of broadleaf trees and the hardened needles of conifer trees ready for the long, cold winter months ahead. What the trees are not ready for, however, is de-icing salt.

In Muskoka, de-icing salts are used on roadways, parking lots and sidewalks to reduce the risk to pedestrians and motorists alike. Salt (sodium chloride) is the most commonly used chemical because it is effective in moderate subfreezing temperatures, is readily available, and is easily applied by business owners and residents.

Urban trees are at the highest risk of damage from de-icing salt. Salty water splashed onto trees from roadways can damage and kill parts of the tree. Salt spray results in trunk lesions, leaf scorch and twig dieback. These symptoms are most prominent on the side of the tree facing the roadway.

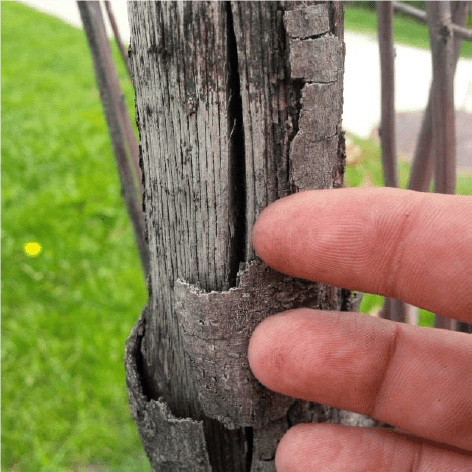

Trunk lesion on a roadside tree caused by de-icing salt. Credit: Javier Cappella.

Leaf scorch caused by salt spray on roadside trees, which resembles winter drying. Credit: Bill Cook.

In a forest, winter drying, warm midwinter weather and drying winds result in brown foliage above the snowline. Credit: Field guide to tree diseases of Ontario.

In a forest, late winter frost after bud break kills the vulnerable new tissue. Credit: Field guide to tree diseases of Ontario.

Trunk lesions are symptoms of continued exposure to salt spray year after year. The exposed bark is coated in salt which works with winter winds to dry out the area and kill that section of the trunk. The result is dead tissue similar to physical damage from equipment or vehicles hitting the tree.

Leaf scorch occurs on conifers that hold their needles through the winter. The dormant trees needles, coated with salt, lose water resulting in the death of the leaf tissue. The needles turn brown and may drop, exposing the twig and buds to more salt damage. Twig dieback results from salt coated buds and twigs dying on both conifers and broadleaf trees.

In a forest setting these symptoms can be seen in the winter as well but for very different reasons. For example, on Crown land (where sustainable forest management works to emulate natural disturbances like wind/insect/fire in how trees are harvested) it is possible to see brown needles on conifers or twig dieback on both conifers and broadleaf trees. Browning of foliage on juvenile trees occurs above the snow line in late winter and is the result of midwinter periods when sunny days stimulate the needles to transpire and lose water as winds dry out the surface of the needles in what is called winter drying. A late frost, occurring after buds break, has a similar effect as salt by killing the new leaves and resulting in twig dieback. Westwind Forest Stewardship Inc. monitors this natural damage in areas that have been harvested to ensure they do not impact the sustainability objectives of forests on Crown land.

While salt spray damage is obvious, the most severe impact of de-icing salts on trees is in the contamination of the soil. Salt deposits from melting snow on pavement accumulates in the soil and negatively affects the soil’s structure, breaking up aggregates and reducing the soil’s permeability and aeration. This makes de-icing salt in the soil the greatest threat to tree health.

In urban soils, it is much more difficult for tree roots to absorb water, nutrients and oxygen. Elevated soil salt levels can lead to severe damage of the tree much quicker than salt spray alone because the de-icing salt in the soil persists through the growing season. Tree decline and mortality is increased with soil contamination caused by de-icing salt that persists in the soil.

In a forest, trees decline and die for a whole host of reasons as part of a healthy forest ecosystem. In urban areas, tree decline and death is disproportionately influenced by de-icing salt. When, how much, and where de-icing salt is used has a significant influence on the health of urban and rural trees. Properly using salt or alternatives not only saves you money and effort, it also helps to reduce the impact of de-icing salt on trees and the environment.

Trees in urban and forested settings contribute to the storage, filtering and flow of water, a critical component of integrated watershed management.

Javier Cappella is a Registered Professional Forester with Westwind Forest Stewardship Inc. and a member of the Muskoka Watershed Council.